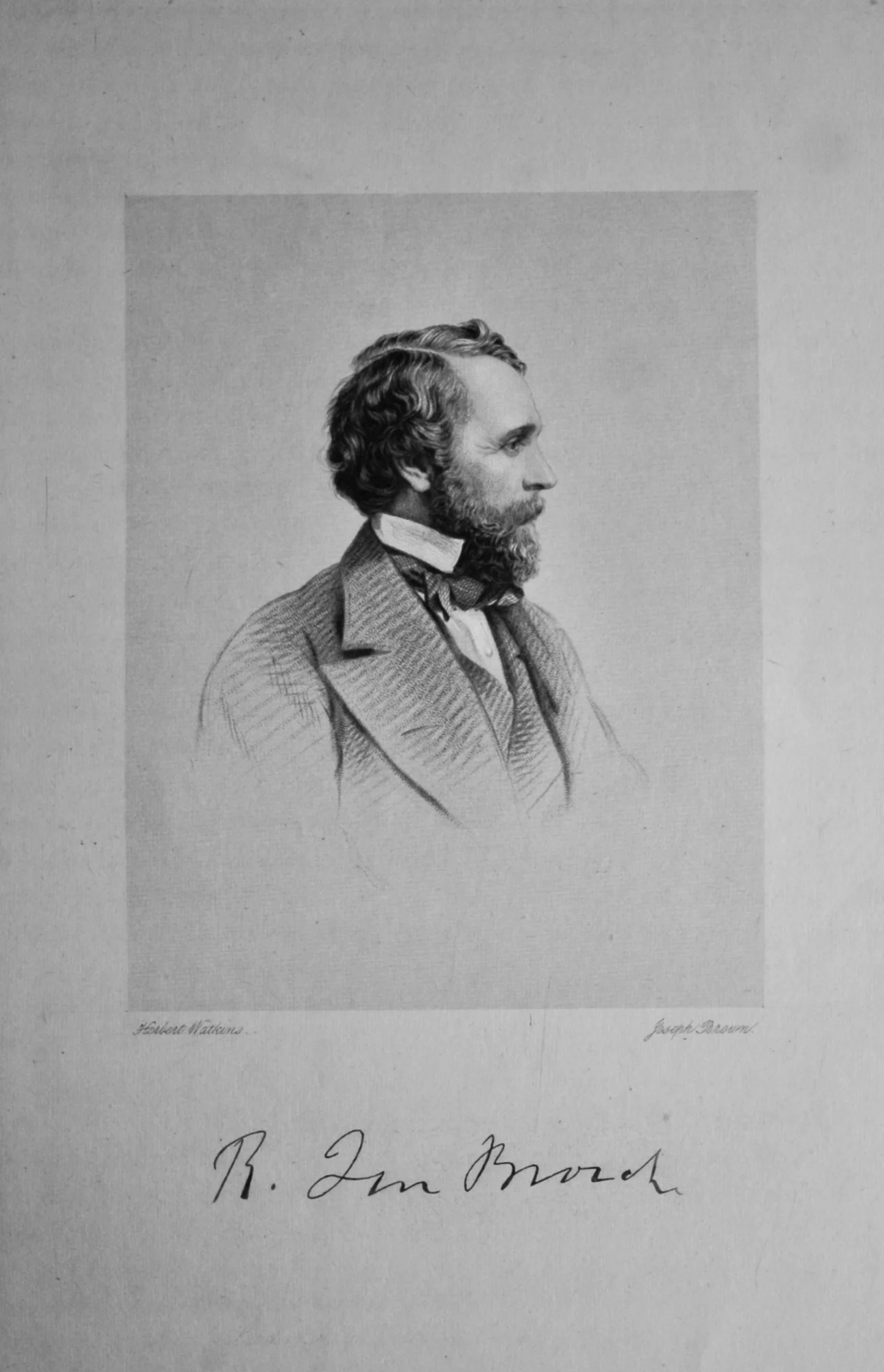

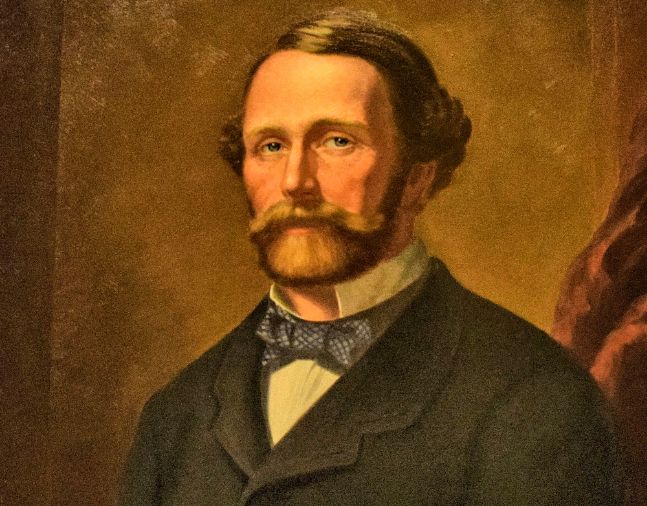

Richard Ten Broeck

Richard Ten Broeck’s deep and fascinating imprint on thoroughbred racing in both America and England “confronts the historian,” John Hervey wrote in Racing in America, 1665-1865, a book commissioned by The Jockey Club. “Fitly to summarize or characterize such a man, and such a career as his, a separate volume would be required.”

2025

Ca. 1811, Albany, New York

Aug. 2, 1892, San Mateo, California

Biography

Richard Ten Broeck’s deep and fascinating imprint on thoroughbred racing in both America and England “confronts the historian,” John Hervey wrote in Racing in America, 1665-1865, a book commissioned by The Jockey Club. “Fitly to summarize or characterize such a man, and such a career as his, a separate volume would be required.”

Simply stated, Ten Broeck was an original — and his stamp on racing was distinctive and has resonated for generations.

Ten Broeck’s racing accomplishments were marveled at. He was celebrated as the owner of Hall of Fame member Lexington, one of the most accomplished racehorses of the 19th century and unquestionably the most impactful stallion in American history. Ten Broeck powered the sport through his successful ownership tenures of multiple southern racetracks, including the famous Metairie Race Course, the grandest track in the country in the pre-Civil War days. He then achieved international acclaim as a pioneering American horse owner who enjoyed success racing in England.

There was also Ten Broeck’s flair for the dramatic and his unconventional adventures such as leaving West Point as a cadet under murky circumstances. He subsequently lived a vagabond life for many years and became a renowned gambler who both won and lost fortunes. Later in life, he descended into periods of mental strife and self-isolation, experiencing a dismal final chapter in an otherwise remarkable existence.

Born into a conservative Dutch family around 1811, in Albany, New York, Ten Broeck graduated from Albany Academy and was accepted in the United States Military Academy in 1829. His tenure at West Point, however, was brief. Less than eight months into his time there, Ten Broeck was recorded as “Resigned, February 28, 1830.” Various reports indicated he assaulted an instructor after perceiving he was being insulted. Ten Broeck then challenged the instructor to a duel that never took place. Normally such behavior would have led to an expulsion, but it is generally assumed the influence of his wealthy family allowed him to resign instead. Ten Broeck’s conduct at West Point led to permanent estrangement from his family.

Little is known about Ten Broeck’s specific whereabouts for much of the next decade, but he supposedly went on the road as a gambler and amassed a fortune. During the late 1830s, Ten Broeck became associated with Col. William R. Johnson of Virginia, one of America’s most renowned racing figures. By 1840, Ten Broeck was racing horses in his own colors of orange and black sash in New Orleans, New York, and St. Louis.

Ten Broeck’s stable began to flourish, and he was becoming known as an influential turfman throughout the South when he took over management of the Bingaman (Louisiana) and Bascombe (Alabama) courses in 1847. In 1851, Ten Broeck purchased Metairie Race Course in New Orleans for $27,000. Under his management, Metairie became the premier track in the country in the decade prior to the Civil War. Ten Broeck increased purses and drew top horses from Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia, and Missouri. He renovated and expanded the track’s grandstand and encouraged the social elite of New Orleans, including women, to support racing by offering lavish facilities.

As a racing promoter, Ten Broeck had few, if any, peers. His greatest promotion of Metairie was the interstate stakes race known as the Great State Post Stake on April 1, 1854. Ten Broeck had traveled to Kentucky the year before looking to buy a colt to run in the race. He purchased the talented Darley, bred and owned by Dr. Elisha Warfield. The colt was renamed Lexington and soundly defeated Lecomte in the Great State Post Stake for $20,000.

In a rematch, Lecomte defeated Lexington (his only career loss) at four miles (setting a world record), but Lexington later lowered that world mark to 7:19¾ in a match against Lecomte’s time. In their third and final meeting, Lexington earned another victory over Lecomte. The mighty son of Boston was regarded as America’s finest horse when retired to stud and went on to become a 16-time leading sire in America. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1955 as part of institution’s inaugural class.

Ten Broeck purchased Lecomte, Prioress, and Starke to race in England, and he became the first American owner to win an important race in that country. Prioress, at quoted odds of 100-1, finished in a triple dead heat in the 1857 Cesarewitch Stakes. Prioress won the run-off, and the victory received extensive coverage in American newspapers as the horse became the first bred and owned by an American to win on the British turf. Prioress also won the Great Yorkshire and Queen’s Plate in England. Ten Broeck pocketed $80,000 betting on Prioress in the Cesarewitch.

Ten Broeck’s English racing “invasion” as reporters called produced mixed results on the track and took a great toll on his stable. Lecomte and Pryor died soon after arriving in the country and Prioress initially struggled with the English racing style, which at the time was more speed-favoring than the American distance events of three to four miles that Ten Broeck’s horses were accustomed to.

Ten Broeck raced in England for around 25 years, experiencing ebbs and flows in his level of success. He was received warmly there and became the first American member in the English Jockey Club. Starke gave him victories in the Goodwood Stakes, Warwick Cup, Brighton Stakes, and Goodwood Cup, among others. With Optimist, Ten Broeck won the Ascot Stakes, Palatine Cup, and Royal Stand Plate.

The efforts of Ten Broeck in British racing paved the way for other American owners to send their horses in England. Pierre Lorillard notably became the first American owner to win a British classic with Iroquois in the 1881 Epsom Derby. Ten Broeck later served as counsel to James R. Keene when he raced Foxhall successfully in England and France, winning the Grand Prix de Paris and Ascot Gold Cup.

Hervey described Ten Broeck as the “uncrowned king of the American sporting world,” and “an elegant figure always fastidiously garbed but without a trace of flash or swagger. In deportment he was cool, quiet, self-contained and bore himself like what in reality he was — a man of high breeding.”

Ten Broeck regularly returned to America between English racing seasons and purchased 525 acres near Louisville, Kentucky, naming it Hurstbourne in honor of the Duke of Portland’s estate in England. While living at Hurstbourne, Ten Broeck’s wife, Pattie, died of cancer in 1873. He remarried in 1877 to Mary Smith, a woman 44 years his junior. The marriage produced two children — a daughter who died during infancy and Richard Ten Broeck III — but the union was volatile, and Mary eventually left.

Estranged from his wife and son, Ten Broeck sold Hurstbourne and moved to San Mateo, California. It was reported he began experiencing mental illness and financial troubles. He became, according to Hervey, “a broken-down man … destitute, soured, embittered, misanthropic, given to fits of ungovernable choler, looking with suspicion and hostility upon humanity en masse.”

Once one of racing’s most essential figures, Hervey said Ten Broeck was “ … in self-chosen solitude and isolation from the world, his only resources the few remaining souvenirs of a vanished past that from time to time he parted with for the means of subsistence.” He died alone in the summer of 1892. Ten Broeck’s body was returned to Kentucky, and he was buried in Louisville’s Cave Hill Cemetery.

Despite the sad final chapter of his life, Ten Broeck was fondly remembered by the newspapers. The San Francisco Call stated, “Internationally looked up to and beloved, the turf and the world in general would be better off if they possessed more men of the stamp of Richard Ten Broeck.”

“He was easy, graceful, and erect in form and figure,” the Charlotte Observer said. “He might have been a commander of an army or occupant of a throne for wherever he appeared he was easily the master of the situation.”

The Louisville Courier Journal added, “Richard Ten Broeck was a man who would hold on at any time against the frowns of fortune, and so he stayed until two nations were electrified by his victory in the Cesarewitch.”

Media