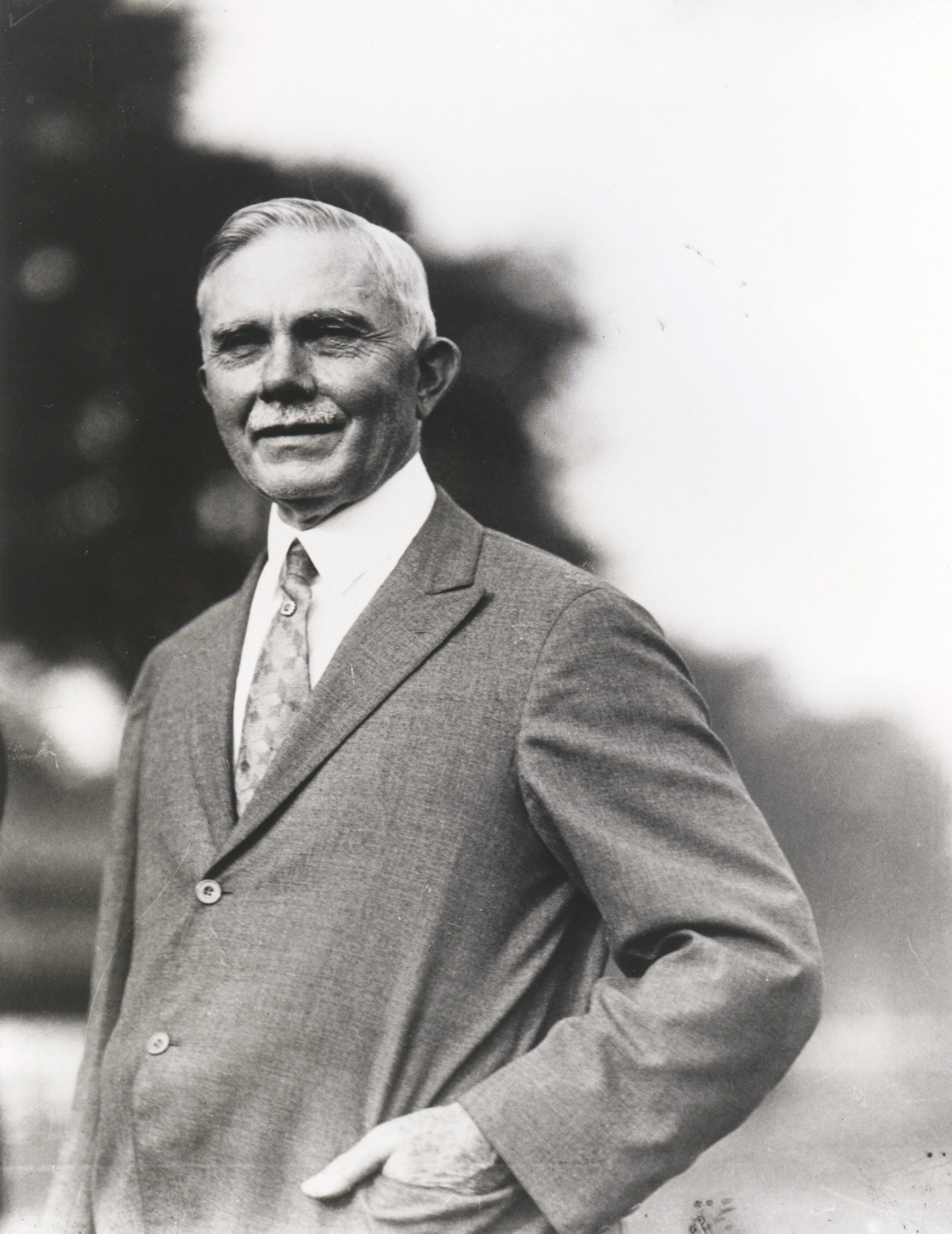

Sam Hildreth: The wild life of a racing legend

Hall of Fame trainer was one of the sport’s most interesting personalities

By Brien Bouyea

Hall of Fame and Communications Director

Even in thoroughbred racing, a sport long known for its stranger-than-fiction characters, Sam Hildreth was considered a wild man. He also happened to be one hell of a trainer — one of the best ever.

As a conditioner of racehorses, it is well chronicled Hildreth had few peers. He was North America’s leading trainer in earnings nine times, won seven editions of the Belmont Stakes, seven runnings of the Brooklyn Handicap, and five renewals of both the Metropolitan and Suburban handicaps.

Hildreth’s proficiency for developing thoroughbreds allowed him to build a sizeable fortune and share the company of racing royalty such as William C. Whitney and August Belmont II, but Hildreth also found plenty of controversy. He was known to pack a pistol (and use it on occasion), drink in excess, engage in brawls, and consort with outlaws.

Samuel Clay Hildreth was born May 16, 1866, in Independence, Missouri. He had five brothers and four sisters and the family never maintained a long-term residence. Hildreth’s father, Vincent, was a farmer and owned a stable of racehorses that competed at fairs throughout the Midwest and Southwest, necessitating a vagabond lifestyle for his family. As a teenager, Hildreth had aspirations of being a jockey, but he grew too big to pursue the endeavor after some early attempts in the saddle.

Around 1882, Hildreth took a job at an establishment with the foreshadowing name of the Belmont Hotel, located in Parsons, Kansas. The owner of the place had a racing stable and the job included training the horses as well as bartending at the hotel. After about four years, Hildreth had saved some money and opened a blacksmithing business with a partner, noting in his memoirs, “there was more money in planting racehorses than training them.”

Hildreth took his blacksmithing business on the road to the Eastern tracks and eventually invested in some bloodstock. His horses were not of the quality needed to race successfully on the New York tracks, so Hildreth sent his runners to New Jersey at places such as Guttenburg, Gloucester, Clifton, and Elizabeth. He began to build his bankroll by winning races and collecting on wagers he made quietly through his betting commissioner, the notorious former outlaw Frank James.

“Scrupulous honesty! That’s what they’d call it in business. When Frank James quit being a desperado he washed the slate clean,” Hildreth said in his memoirs. “He was going straight as a string when I knew him, and there were plenty of chances for him to cheat me. You’d never have suspected Frank James of being one of the notorious brothers who held up trains and caused a reign of terror through the Middle West in the early days. He looked more like a country storekeeper or farmer.”

Hildreth enjoyed moderate success as a trainer and owner throughout the 1890s before a big break came right before the turn of the century when Whitney hired him to work for his emerging stable. Hildreth’s first major victory came with the Whitney-owned Jean Bereaud in the 1899 Belmont Stakes, but the relationship between the trainer and owner deteriorated quickly.

There are multiple versions of the tale, but Whitney dismissed Hildreth as his trainer in the fall of 1900, around the time Hildreth engaged in an ugly brawl with fellow trainer John E. Madden. One account claimed a drunken Hildreth was firing a pistol around the Morris Park clubhouse after punching a waiter when he encountered Madden. Hildreth supposedly struck Madden in the head with a walking stick and the two proceeded to slug it out. The ramifications included Whitney firing Hildreth and the trainer having his New York racing license pulled by The Jockey Club.

Hildreth had a reputation as being a combative sort and was known as a heavy drinker (although later in life he quit drinking altogether). His encounter with Madden was not a surprise, as Hildreth had been fined and suspended multiple times because of his temper before Whitney dismissed him and made sure his New York training license was revoked.

Banned from the metropolitan tracks, Hildreth took the string of horses he owned (reported at 30) and went to compete in Chicago, New Orleans, and Memphis. Hildreth was secure financially at the time, as it was reported in the New York Times that he had won $250,000 in purses and bets in 1900 from May through October. The horses he owned were worth an additional $100,000 according to the report.

Following a series of various ups and downs as a wandering horseman in the next few years, Hildreth was able to go back to New York upon Whitney’s death in 1904. Hildreth eventually returned to prominence in New York thanks in large part to his purchase of the colt Fitz Herbert for $10,000 in 1908.

After winning three times for Hildreth as a 2-year-old in 1908, Fitz Herbert won 14 of 15 races in 1909, including the Lawrence Realization and the Jerome and Suburban handicaps. It was a most prosperous time for Hildreth, who also won his second Belmont that year with another horse he owned, Joe Madden. Hildreth topped the North American trainer list at $123,942 in earnings and the owner list with $159,112 in 1909. He also topped both categories in 1910 and 1911.

With New York racing shut down in 1911 because of anti-gambling legislation, Hildreth spent the year headquartered in Canada before heading to France in 1912 with a string of horses for owner Charles Kohler. Hildreth enjoyed his time in France — and even purchased a lavish French chateau — but Kohler died in June 1913 and Hildreth had no reason to stay overseas. At the time of Kohler’s death, August Belmont II happened to be in Paris and convinced the trainer to return to America in his employ, as racing was returning to New York.

“There’s no place like home. I was anxious to see the old familiar faces again in the paddocks,” Hildreth said. “I was itching for somebody to come along and give me a hard slap on the back and shoot a few American cuss words in my direction. It wasn’t because I didn’t like France especially, but because I do like America particularly.”

And so 15 years after he was blackballed in New York by one of the sport’s most prominent individuals, Hildreth was hired by Belmont, another racing titan and the Chairman of The Jockey Club. To say Hildreth was thrilled was an understatement.

“Back in my old haunts, among my old friends, and the old scenes just as they were before we’d gone to Europe. It was a beautiful summer day, the day of our return, and the fragrance of the flowers and the soft beauty of the green shrubbery lining the walks of the Saratoga race course,” Hildreth said. “The flags flying and the band up there in the grandstand … all of it gave me a thrill that comes once in a lifetime. Maybe my friends will not say I’m a demonstrative fellow, but I was so tickled by it all that I could have danced around and given three rousing cheers, all by myself.”

In both 1916 and 1917, Hildreth trained the champion 3-year-old of the year, Friar Rock and Hourless, respectively, for Belmont. Both won the Belmont Stakes, pushing Hildreth’s total to four wins in the event. Hildreth went on to win the Belmont in 1921 (Grey Lag), 1923 (Zev), and 1924 (Mad Play) for Harry F. Sinclair’s Rancocas Stable to give him a total of seven victories in the race. Only James Rowe, Sr. (eight) has won the Belmont more times than Hildreth. Following his three-year run (1909 through 1911) as North America’s leading owner and trainer, Hildreth again topped the trainer standings in earnings in 1916, 1917, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924. He also led all trainers in wins in 1921 and 1927.

Grey Lag and Zev — both future Hall of Fame members — were Hildreth’s top runners of the era. For Hildreth, Grey Lag won the Brooklyn, Metropolitan, Saratoga, Empire City, Queens County, Knickerbocker, and Excelsior handicaps in addition to the Belmont. Zev, meanwhile, added wins in the Hopeful, Grand Union, Withers, Lawrence Realization, Queens County, and a famous 1923 match race against Epsom Derby winner Papyrus before a crowd of 50,000 at Belmont Park. Zev also won the Kentucky Derby, but that victory was credited to David J. Leary, Hildreth’s assistant.

Zev, the first horse to surpass $300,000 in career earnings, was the 10th and final champion trained by Hildreth, joining Jean Bereaud, Fitz Herbert, King James, Novelty, Dalmatian, Friar Rock, Hourless, Mad Hatter, and Grey Lag. Mad Hatter ($194,525), Grey Lag ($136,675), Mad Play ($136,432) and King James ($103,405) also earned more than $100,000 in their respective careers, a considerable sum for the time.

Hildreth began to experience stomach issues in the late 1920s and died in New York City after an abdominal surgery on Sept. 24, 1929, at the age of 63. He was buried only a few blocks from Saratoga Race Course at Greenridge Cemetery. Hildreth’s estate was valued at more than $1 million. He was survived by his wife, Mary.

Hildreth’s legacy was a mixed bag. Upon his death, Neil Newman wrote in the National Turf Digest, “It has been said of Samuel Hildreth that he had as much skill and as little class as any trainer that ever saddled a horse.”

J. K. M. Ross, however, said Hildreth’s “heart and manner were gentle; courtesy was his hallmark.” Nelson Dunstan added, “The late Sam Hildreth had a genuine affection for horses. Not necessarily racehorses, but all horses regardless of breeding.”

Frank Catrone, who rode for Hildreth in his youth and later trained Kentucky Derby winner Lucky Debonair, said Hildreth “never permitted sentiment to sway his judgement or his heart, and horses and men were only tools of the trade to be used and then cast aside when their value was done.”

In an example of the many contrasting opinions of Hildreth, Catrone, later in the same interview, said Hildreth “loved horses and animals. No thoroughbred in his care ever was mistreated, and he poured out the same lavish attention on other members of the backstretch menagerie that cluttered up his stable aisles.”

While a variety of opinions existed about Hildreth’s character there is no disputing his life was an incredible journey.

From humble Midwest beginnings, Sam Hildreth climbed to the top of New York racing before suffering a self-inflicted fall from grace. He worked his way back up, ventured to France, stood atop New York racing a second time, and left behind a remarkable legacy in the sport that led to his enshrinement in the Hall of Fame as a member of the inaugural class in 1955.

SAM HILDRETH

Born: May 16, 1866, Independence, Missouri

Died: Sept, 24, 1929, New York City

Notable:

- North America’s leading trainer by earnings 1909, 1910, 1911, 1916, 1917, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924

- North America’s leading trainer by wins 1921, 1927

- North America’s leading owner by earnings 1909, 1910, 1911

- Won the Belmont Stakes 1899 (Jean Bereaud), 1909 (Joe Madden), 1916 (Friar Rock), 1917 (Hourless), 1921 (Grey Lag), 1923 (Zev), 1924 (Mad Play)

- Won the Brooklyn Handicap 1909 (King James), 1910 (Fitz Herbert), 1916 (Friar Rock), 1920 (Cirrus), 1921 (Grey Lag), 1923 (Little Chief), 1925 (Mad Play)

- Won the Metropolitan Handicap 1909 (King James), 1915 (Stromboli), 1921 (Mad Hatter), 1922 (Mad Hatter), 1923 (Grey Lag)

- Won the Suburban Handicap 1909 (Fitz Herbert), 1915 (Stromboli), 1916 (Friar Rock), 1923 (Gray Lag), 1924 (Mad Hatter)

- Won the Jockey Club Gold Cup 1919 (Purchase), 1921 (Mad Hatter), 1922 (Mad Hatter)

- Won the Travers Stakes 1910 (Dalmatian), 1922 (Little Chief)