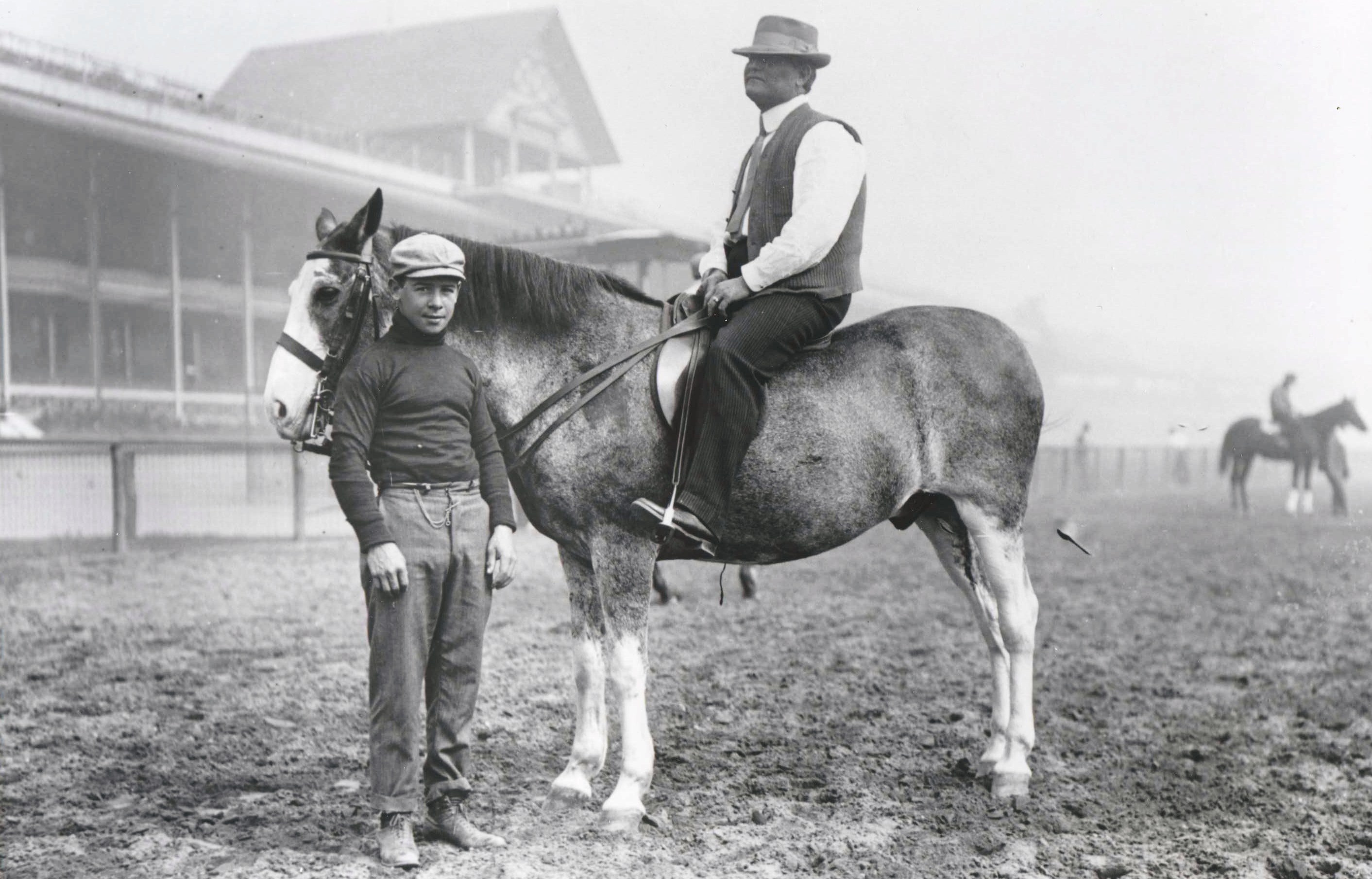

The incomparable James Rowe, Sr.

A masterful horseman, Rowe trained more champions (34) and Hall of Famers (10) than anyone in American history

By Brien Bouyea

Hall of Fame and Communications Director

James Gordon Rowe was one of the finest jockeys in America during the 1870s, winning such prestigious races as the Belmont, Travers, Saratoga Cup, and Jerome Handicap, among others. He was the nation’s leading rider from 1871 through 1873 and became the regular jockey — at the age of 14 — for one of the greatest horses of the 19th century, Harry Bassett.

As distinguished as they are, Rowe’s achievements in the irons are a mere footnote in a much bigger story. When he could no longer make weight as a jockey, Rowe made the transition to training thoroughbreds. It proved to be his life’s calling.

In a training career that spanned 50 years, Rowe established himself as the most accomplished conditioner of racehorses in American history. He developed more champions (34) and Hall of Fame members (10) than any other individual in the sport’s annals. Rowe won every major event in America, including a record eight runnings of the Belmont, a race he also won twice as a jockey. He also won multiple editions of the Futurity (nine), Alabama (seven), Brooklyn Handicap (six), Saratoga Special (five), Manhattan Handicap (five), Gazelle (five), Dwyer (four), Hopeful (four), Metropolitan Handicap (three), Travers (three), and Kentucky Derby (two), among others.

Rowe was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1857. At the age of 10, he was working at a newsstand at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond when he was spotted by Col. David McDaniel, who invited the youngster into his stable as an apprentice rider. McDaniel had a keen eye for talent. He owned a racetrack in New Jersey, as well as a stud farm, and his stable topped the owners’ list from 1870 through 1874. Rowe learned the ropes from one of the best.

By the time he was 14, Rowe had demonstrated a rare combination of strength and finesse in the saddle, as well as a tremendous sense of timing. Those skills convinced McDaniel that Rowe was the ideal pilot for the great Harry Bassett. It was a perfect pairing. As a 3-year-old in 1871, Harry Bassett was undefeated in nine starts. Rowe was aboard for victories in the Jerome, Kenner and Dixie, among others.

Rowe made quite a name for himself in 1871. At Jerome Park, McDaniel put him aboard a talented 3-year-old colt named Abd-El-Koree in a four-mile race. Rowe, who could ride at 95 pounds, broke quickly to get the lead on Helmbold and Billy Lakeland, a famous jockey of the day. Helmbold closed the gap late, but Rowe and Abd-El-Koree held on to win by a neck and set a world record of 7:33 for a 3-year-old at the distance.

One contemporary account described Rowe as “holding Koree together with the skill of a veteran” and that “little Rowe came in for even greater credit than the horse. It was a great race, won by a gallant colt and a clever lad.”

In 1872, Rowe guided Harry Bassett to victory in the 2¼-mile Saratoga Cup against Longfellow, who was described by historian Walter Vosburgh as “beyond question the most celebrated horse of the 1870s.” Longfellow struck himself on the left front hoof going to the post, and the bent shoe dug into his hoof, causing considerable pain. Longfellow’s efforts under duress were heroic, but they certainly did not diminish the spectacular display Harry Bassett put on that day. He established the fastest time on record for 2¼ miles, 3:59.

Rowe also had the good fortune of riding Joe Daniels in 1872, winning the Belmont and Travers. Rowe won the Belmont again in 1873 with Springbok. He had emerged as arguably the best rider in America, but his days as a jockey were nearing an end.

Increasing weight forced a premature end to Rowe’s career in the saddle. In his late teens, Rowe went to New York City for a spot in P. T. Barnum’s Great Roman Hippodrome. Yes, he joined the circus, riding in races and participating in other equestrian events in front of crowds that regularly topped 10,000.

After his stint with Barnum, Rowe returned to the racetrack. In 1878, he landed his first marquee job as head trainer for Mike and Phil Dwyer, brothers who grew up poor before making a fortune as wholesale butchers in Brooklyn, New York. The Dwyer brothers came out of nowhere to take the sport by storm. George and Pierre Lorillard had been dominating racing in the East for almost a decade, but the Dwyers jumped right into the New York thoroughbred scene, giving the sport a new powerhouse stable.

For the Dwyers, Rowe trained future Hall of Fame members Hindoo, Luke Blackburn, and Miss Woodford, as well as standouts Bramble, George Kinney, Onondaga, and Runnymeade, among others. Rowe had an embarrassment of riches to work with through his association with the Dwyers.

Before being purchased by the Dwyers, Luke Blackburn won only two of 13 starts as a 2-year-old in 1879. However, once in the care of Rowe, Luke Blackburn realized his potential. In one of the most remarkable campaigns in American racing history, Luke Blackburn won 22 of 24 starts in 1880, including 15 in a row. The Dwyers had no interest in breeding, so if their horses were able to run, that’s exactly what they did. At one point, Luke Blackburn had seven starts in 19 days in 1880. That same year, Rowe was developing a promising 2-year-old for the Dwyers named Hindoo.

After winning seven of nine starts in 1880, Hindoo won 18 consecutive races from May through August 1881. His victories included the Kentucky Derby, Clark Handicap, Tidal, Coney Island Derby, Travers, Kenner, and Champion. In typical Dwyer brothers fashion, Hindoo won four races at Saratoga in 1881. Only two days after winning his final Spa start that summer, the Kenner, Hindoo was sent to Monmouth Park, where he defeated the Lorillard brothers’ Monitor and Parole. Three days later, Hindoo added the Jersey St. Leger.

The frequent action eventually took its toll on Hindoo, as he dropped his final two starts at age 3 and his first start at 4. However, he rebounded to close out his career with five consecutive wins, including the 2½-mile Louisville Cup and the 2¼-mile Coney Island Cup. Hindoo was retired with a record of 30-3-2 from 35 starts. He leads off just about any discussion when it comes to the greatest American thoroughbreds of the 19th century.

Miss Woodford arrived on the scene in 1882. Arguably the top filly or mare of the 19th century, Miss Woodford fashioned a 16-race win streak and became the first American thoroughbred to surpass $100,000 in career earnings. She was undefeated at age 4, including a victory on the Great Long Island Stakes against Modesty, winner of the Kentucky Oaks and American Derby. Miss Woodford won in consecutive heats of two miles. Her combined time of 7:04¼ set the American record.

Rowe wanted to give Miss Woodford some time off when she lost three consecutive races at age 5. Phil Dwyer, however, objected. Turf writer Ed Heffner reported Miss Woodford had developed a leg problem, but Phil Dwyer demanded Rowe to run her.

“If she starts, I’m through,” said Rowe, according to Heffner.

So ended Rowe’s association with the Dwyer brothers.

Rowe trained for various owners in the next few years before being hired by August Belmont, whose stable had been in decline for a few years since the head of his operation, Jacob Pincus, went to work for Pierre Lorillard. Rowe quickly resurrected Belmont’s stable, developing the top 2-year-old colt (Potomac) and filly (La Tosca) of 1890. The success, however, was short lived. Belmont died in November 1890 and his stable was dispersed at auction by the end of the year.

After Belmont’s death, Rowe spent some time as a racing official in California before returning to training. In 1899, Rowe went to work for James R. Keene, whose stable, like Belmont’s, had fallen on hard times. Just as he did for Belmont, Rowe helped Keene return to the sport’s upper echelon. Rowe developed five future Hall of Famers for Keene: Colin, Commando, Maskette, Peter Pan, and Sysonby.

Colin was Rowe’s favorite. Undefeated in 15 career starts, Colin won 12 times at age 2 and added a victory in the Belmont at 3 before being retired with an injury. Rowe held Colin in such high regard that he once quipped he wanted his epitaph to read only “He trained Colin.”

Racing in New York was shut down in 1911 and 1912 because of anti-gambling legislation. Many of the top owners and trainers went to Europe, but Rowe remained stateside. Keene died in 1913 and his stable was dispersed, but Rowe had already lined up his next major client, Harry Payne Whitney.

Of the 11 champions he trained for Whitney, the super filly Regret was the most remarkable. As a 2-year-old at Saratoga in 1914, Regret won the Sanford, Saratoga Special and Hopeful, defeating colts in each race. The following spring, Regret became the first filly to win the Kentucky Derby. Her victory in the Derby helped establish the race as an elite event in American racing.

Rowe had many more years of success training for Whitney through the 1920s. He won the Preakness in 1921 with Broomspun to give him a total of 11 victories in the series of races that would later be known as the Triple Crown (13 counting his two victories as a jockey in the Belmont). Rowe led all trainers in earnings four times in the 1920s.

Attention to detail was a major factor in Rowe’s success. Mose Goldblatt, who conditioned a secondary string of horses for Whitney, said Rowe’s work ethic was unrivaled.

“Rowe was a tough taskmaster. He neither spared himself or his helpers. Up before light every day of the year, no matter what the weather might be, he always had his help up and doing,” Goldblatt said. “When an ailing horse required his personal attention, he would stay with it indefinitely.

“He got used to sleeping in box stalls when he was a stable boy and budding jockey back in the ’70s. He found it just as easy to make himself comfortable in a box stall after he turned 70, when there was need of his presence at the stable, as he had when he was a kid. But exacting as he was, his help all loved and respected him. No man ever got more willing service out of hands of all sorts.

“And no man ever had about him men of more intelligence. He employed no dumbbells. Once a man won a place in his organization he kept it because he deserved it. He made it plain to all that handling high-spirited thoroughbreds was a delicate matter that required diligent as well as intelligent attention.”

Rowe had been suffering from an aggravated neuritis condition for several months when he died at the age of 72 in Saratoga on Aug. 2, 1929. He still made it to the races and attended to his stable until about two weeks before he died. On his way to the hospital, Rowe said to fellow trainers and close friends Tom Healey and A. J. Joyner, “This is my last ride. I’ve fought it as long as I can and I know I’ll never come back.”

“I felt he was gone when he left the house,” said Marshall Lilly, a longtime assistant to Rowe. “He came down the steps with his eyes on the ground and then halted for a minute, raising his head for a last look about the stables, shaking his head sadly as if saying goodbye.

“Not a word did he speak before dropping his head and walking off to the car. It was his farewell to the stable and the employees who served him faithfully for so many years.”

R. T. Wilson, president of the Saratoga Racing Association, said, “It is with the deepest regret that I learned of the death of Mr. Rowe. What we of the organization think of him may be judged from the half-masting of our flags, something we have never done for another trainer.”

Rowe was inducted into the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame as part of the institution’s inaugural class in 1955. He was joined that year by one of his early standouts, Hindoo. Five more Rowe trainees — Colin, Commando, Luke Blackburn, Peter Pan, and Sysonby — were inducted in 1956. Regret (1957), Miss Woodford (1969), Whisk Broom II (1979), and Maskette (2001) followed.

In 2010, Harry Bassett, the first great horse Rowe was associated with, was inducted into the Hall. Rowe once said he wanted his epitaph to read, simply, “He trained Colin.” But Rowe’s incomparable legacy in thoroughbred racing encompassed so much more and three words fail to do justice for a remarkable life in racing. The first three words engraved on Rowe’s Hall of Fame plaque in the National Museum of Racing, however, are a powerful start: America’s greatest trainer.

JAMES ROWE, SR.

Born: 1857, Richmond, Virginia

Died: 1929, Saratoga Springs, New York

Notable:

- Leading jockey in America 1871, 1872, 1873

- North America’s leading trainer by earnings 1908, 1913 1915

- Trained 10 Hall of Fame members: Colin,

Commando, Hindoo, Luke Blackburn, Maskette,

Miss Woodford, Peter Pan, Regret, Sysonby, and Whisk Broom II

American Classic wins as a trainer:

Kentucky Derby (2) — 1881 (Hindoo), 1915 (Regret)

Preakness Stakes (1) — 1921 (Broomspun)

Belmont Stakes (8) — 1883 (George Kinney),

1884 (Panique), 1901 (Commando), 1904 (Delhi),

1907 (Peter Pan), 1908 (Colin), 1910 (Sweep), 1913 (Prince Eugene)

* also won the Belmont twice as a jockey with Joe Daniels (1872) and Springbok (1873)

Other major wins as a trainer:

Futurity Stakes (9) — 1890, 1897, 1899, 1907, 1908, 1909, 1913, 1915, 1921

Alabama Stakes (7) — 1882, 1883, 1909, 1919, 1921, 1922, 1926

Brooklyn Handicap (6) — 1901, 1905, 1907, 1908, 1913, 1917

Saratoga Special (5) — 1904, 1914, 1915, 1920, 1922

Manhattan Handicap (5) — 1887, 1890, 1914, 1926, 1928

Gazelle Stakes (5) — 1890, 1903, 1907, 1909, 1917

Dwyer Stakes (4) — 1898, 1900, 1907, 1916

Hopeful Stakes (4) — 1906, 1908, 1914, 1915

Travers Stakes (3) — 1881, 1883, 1909

Metropolitan Handicap (3) — 1905, 1913, 1920

Saratoga Special (2) — 1914, 1919